|

| General Washington at Trenton, as depicted by Charles Wilson Peale |

While Washington is one of the best known

presidents, very little about his personality is common knowledge to modern

Americans. Even the enduring picture we have of Washington, on the dollar bill, is a painting of a man at the end of his life and haggard by political

infighting that marred his second presidential term.

What follows are some of the anecdotes about Washington’s character, from Chernow’s book, that stuck with me.

It is evident that Washington was obsessed by status. He

disliked the lack of respect shown to colonists by the British. Young Washington gained acclaim in the French and Indian War, however it angered him

that he was never awarded the royal commission that he both desired and lobbied

for. Additionally, letters to the London firm with which Washington traded to

obtain the wares of British aristocracy show a man who was deferential despite persistent suspicions that he was being ripped off. It is disconcerting to know

that the man who commanded the Continental Army and drove the British from the

United States yearned for their approval. It would be an interesting exercise

in the counterfactual to consider how American history may have been altered

had Washington received that royal commission.

As a general, Washington enforced discipline in a way that

is shocking to the modern reader. He whipped retreating soldiers from his horse

during battle, ordered soldiers to publicly execute mutinous comrades, and

often exposed himself to danger on the front lines of battle. This isn’t meant

to paint the picture of a cruel or cavalier general. It is important to realize

that the “army” he commanded was vastly outnumbered, underfed, underclothed, and

un-or-underpaid. Washington shouldered two unimaginable burdens, holding the

army together and thwarting the British. He battled rampant illness and short

assignments that had him training a seemingly new army each spring. Washington loved

the men who stuck with him. He fought for better provisions and payment, he did

not hide from danger behind his men, and he personally signed thousands of the

discharge letters at the war’s end.

|

| Federal Hall in New York City: The site of Washington's first inauguration |

Washington, the president, was very conscious of the

precedents that he would be setting. He is often portrayed as a reluctant

president, and in some ways he probably was. It was a shocking display of

republican values that Washington could resign his generalship after the war.

He feared that accepting the presidency would confirm to the world that he was just as power hungry as successful generals before him, not the Cincinnatus

Americans saw him as. At the beginning of his generalship, presidency of the Constitutional

Convention, and presidency of the United States, Washington made it clear that

he had been compelled to do the job. Whether he wanted nothing more than to

live out his days at Mount Vernon, he was a masterful politician, or something

in between, there is no doubt that he was extremely sensitive about how history

would view him. The thought that the country he had given much of his life to

help form might require his stewardship to incubate its new government likely

left him feeling that he had no choice but to serve. For a man who was

unanimously elected president three times (Constitutional Convention and twice

as President of the United States), the partisanship between Jeffersonians and

the Hamiltonians (i.e. the republicans and the federalists) that took form during

his second term was difficult on Washington and quickly wore him down both mentally

and physically.

|

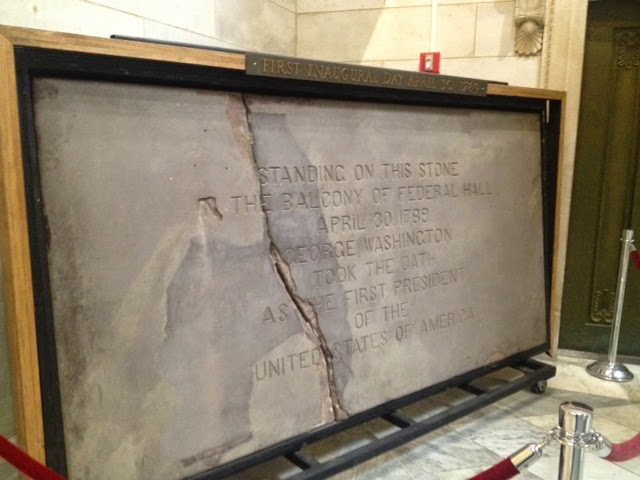

| Inside Federal Hall are many Washington relics including this stone slab on which Washington stood during his first inauguration. |

The issue of slavery is the most troubling aspect of Washington’s character. Washington clearly knew he was on the wrong side of history as a slave owner. He spoke of manumission with abolitionist peers such as Lafayette. Hamilton, maybe not worthy of the title abolitionist, also pushed Washington against slavery. However, Washington never made the stand against slavery that he could have. His signing of the Fugitive Slave Act, efforts to capture slaves that escaped from Mount Vernon, and ability to tailor his views on slavery to fit his audience paints a picture of a man who recognized the contradiction of slavery in the new republic but did not believe the young nation or his personal finances could afford to challenge the institution. In a final act of courage on the issue, or perhaps cowardice, Washington’s will called for the emancipation of his slaves upon Martha’s death. She ultimately freed them soon after Washington died.

No comments:

Post a Comment